-

>

心灵元气社

-

>

县中的孩子 中国县域教育生态

-

>

(精)人类的明天(八品)

-

>

厌女(增订本)

-

>

这样学习才高效/杨慧琴

-

>

心理学经典文丛:女性心理学

-

>

中国文化5000年

礼貌语用学 版权信息

- ISBN:9787544649995

- 条形码:9787544649995 ; 978-7-5446-4999-5

- 装帧:一般胶版纸

- 册数:暂无

- 重量:暂无

- 所属分类:>

礼貌语用学 内容简介

本书作者把绝对礼貌称作“语用语言学礼貌”, 对之前的模式进行改造, 在兼顾”社会语用学礼貌“的同时, 重点论述了语用语言学的礼貌。

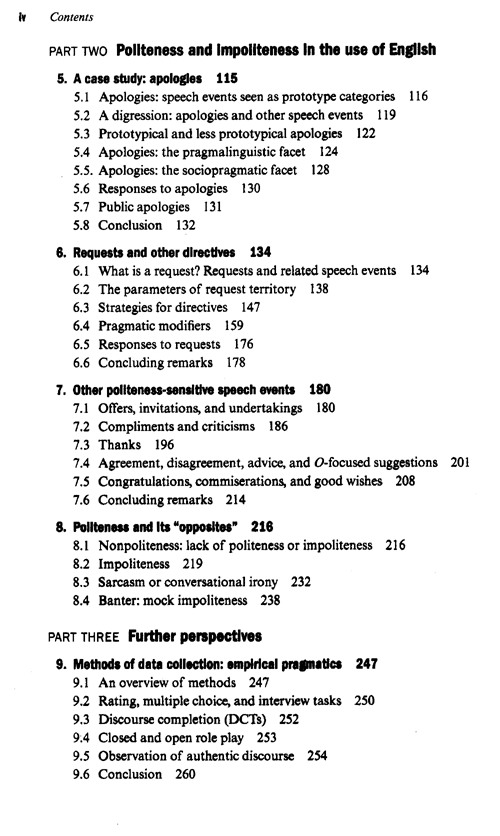

礼貌语用学 目录

礼貌语用学 节选

《牛津社会语言学丛书:礼貌语用学》: Gu's reworking of my Generosity Maxim opened my eyes to a fiaw in the 1983 model; also his Balance Principle, which recognizes the important element of balance or equilibrium underlying mutual politeness, needs to be recognized as an essential component of why people are polite. Other writers, such as Watts and Spencer-Oatey, also recognize this The idea that politeness is normative comes out particularly strongly in the conversational contract view of Fraser and Nolen, but it is also an essential feature of other models, including my own. As I see it, the nature of sociopragmatic politeness (as opposed to pragrnalinguistic politeness) involves convergence on, or divergence from, a norm of what is regarded as appropriately polite for a given set of situational parameters The normative nature of politeness has been questioned by Eelen (2001), because it appears to make the exercise of politeness an impediment to the individual's freedom of behavior. However, awareness of a norm does not compel obedience to a norm. Certainly a norm is not to be seen as some kind of superimposed restriction on behavior. Empirically, I see no problem in recognizing the existence of statistically observable politeness norms (as shown, for example, by convergent responses to discourse completion tasks and multiple choice questionnaires") as a background against which individual performances can deviate Moreover, we carry around with us some contextually tunable sense of what is normal politeness as part of our social-co8:nitive response to communicative situations When the comment is made that a person is "very polite," or "a little bit rude," and so on, we are implicitly acknowledging; such a norm, from which individuals' behavior can deviate in a positive or negative direction. Arndt and Janney lay great store on the responsiveness of the whole person in politeness; for them, the purely linguistic aspect of politeness must be integrated with other components of interpersonal emotive communication, including prosody, paralinguistics, gesture, eye gaze, kinesics, and proxemics. I recognize the importance of these additional channels of communication, and in fact it has often been commented that the nonlinguistic channels may be more important for impressions of politeness than the actual words said. At the same time, I have to admit that little space in this book will be devoted to these features, which demand a rather different research paradigm. My two excuses for largely omitting nonlinguistic and prosodic aspects of politeness are that my research endeavor does not extend beyond the linguistic, and that the corpora I have mainly used for examples do not provide paralinguistic or prosodic information. On the other hand, Arndt and Janney's characterization of politeness in terms of supportiveness is something I find compatible with my General Strategy of Politeness (GSP; 4.3), which identifies politeness with the assigning of high value to the other person's concerns and Iow value to one's own. Indeed, the two ideas are very closely associated: being supportive means giving compatbetic support-something of value-to another person. Amdt and Janney's approach in particular highlights the importance of one of the constituent maxims of the GSP: the Sympathy Maxim, which focuses especially on the goal of identifying one's own feelings with the feelings of the other. Ideals distinction between Discernment and Volition as two types of politeness, the former more associated with Eastern cultures and the latter with Western cultures, corresponds in essence to my distinction between bivalent and trivalent politeness (1.2.1), the former being richly developed in languages such as Japanese that have elaborate honorific systems, I also see these bivalent and trivalent conceptions of politeness as leaning respectively toward a sociolinguistic domain and a pragmatic one. As opposed to pragmatics, sociolinguistics tends to deal with variables that are relatively stable across time (Thomas 1995: 185-187): variables such as the gender, age, social networks, and social relations as measured according to B&L's P and D factors Hence bivalent politeness ("discernment"), with its social indexing function, belongs here rather than to pragmatics. On the other hand, trivalent politeness ("volition"), dealing with dynanuc 8oal-driven communicative behavior, belongs more to pragmatics The goal-driven nature of trivalent politeness is likely to vary from one encounter to another, depending on the individual goals, as well as social goals, adopted by S. However, the two politenesses are not separate, and honorific usage can interact dynamically with context, as has been shown for Japanese by Okamoto (1999). ……

- >

我与地坛

我与地坛

¥15.4¥28.0 - >

诗经-先民的歌唱

诗经-先民的歌唱

¥18.7¥39.8 - >

二体千字文

二体千字文

¥21.6¥40.0 - >

苦雨斋序跋文-周作人自编集

苦雨斋序跋文-周作人自编集

¥6.9¥16.0 - >

随园食单

随园食单

¥21.6¥48.0 - >

新文学天穹两巨星--鲁迅与胡适/红烛学术丛书(红烛学术丛书)

新文学天穹两巨星--鲁迅与胡适/红烛学术丛书(红烛学术丛书)

¥9.9¥23.0 - >

巴金-再思录

巴金-再思录

¥14.7¥46.0 - >

回忆爱玛侬

回忆爱玛侬

¥9.8¥32.8

-

字海探源

¥25¥78 -

《标点符号用法》解读

¥8.3¥15 -

文言津逮

¥10.2¥28 -

那时的大学

¥12¥28 -

现代汉语通用字笔顺规范

¥19.6¥58 -

2020年《咬文嚼字》合订本

¥23.8¥60